Roger Federer Returned to the Spotlight this Summer, and Reminded us why he Continues to Matter

“He’s really letting himself go, isn’t he?” Jim Courier joked in the commentary booth when the cameras spotted Roger Federer in a suite at the US Open earlier this week.

The line made Courier’s broadcast partner, Mary Carillo, laugh out loud, because it was so perfectly preposterous. Everyone who got a glimpse of Federer in that moment likely had the same reaction: “Wow, Fed looks great.” His hair was thick and cut short. His skin was tan, his face youthful, his body trim, his clothes stylish, his grin as wide as ever. And just like when he was a player, he did it all without looking like he was trying too hard. Federer’s manner and appearance seemed like a cheerful challenge to the aging process.

No great athlete ever wants the applause to stop—Federer included. But most of his fans felt that if anyone could take retirement in stride, and find satisfaction in the next phase, it would be this most level-headed and naturally upbeat of players. That has proven true this summer, when Federer reemerged on three fronts—as a public speaker, as the subject of a documentary about the final days of his career, and as the title character of a deluxe coffee-table book by Assouline that was published this week. Together, they summed up Federer’s career, revealed new aspects of it, and gave us reasons for why he will continue to matter.

Federer the Wise

He opened the summer by, as he said himself, venturing outside his comfort zone. On a drizzly June day in New Hampshire, he gave Dartmouth’s commencement speech, to a class that included the daughter of his agent, Tony Godsick. Federer admitted to being nervous at the start, but, like all good commencement speakers, he used it as part of his lesson about being willing to try new and potentially nerve-wracking pursuits.

Once the early jitters subsided, Federer grew more confident as he came to the meat of his speech. The high point was his calculation that, even as one of the world’s best tennis players for many years, he had won just 55 percent or so of the points he had played. The line—and its lessons about not aiming for perfection, and not letting failure stop you—went viral. It’s a fact that people outside of tennis were stunned by, and one that young pros on tour have begun to quote as a way of motivating themselves to make small improvements in their games.

Federer was always elegant and artful in his motions. At Dartmouth, he showed that he can think and speak with equal grace.

Federer the Human

A week or so after his Dartmouth speech, Amazon Prime released Federer: 12 Final Days, a British documentary directed by Asif Kapadia and Joe Sabia. As the title tells us, the movie is about the end of Federer’s career, from the day he announced his retirement to the day it finally, tearfully happened at Laver Cup in London.

At his peak, Federer was a sporting representation of perfection. Nothing could touch him, no one could beat him, he barely sweated, his clothes and hair and playing style were immaculate, and he didn’t have ailments like his mere mortal colleagues. In more than 1,400 career matches, Federer never retired due to injury.

In 12 Final Days, we can see that once upon a time, Federer wanted to believe in his own myth.

He says that he never thought he would have surgery. That if he was ever hurt, he would take time off until it healed. That philosophy worked for most of his career, until it didn’t. In 2016, while he was giving his kids a bath, he felt a click in his knee. That led to surgery, and a successful comeback. But then there was another knee injury, and another, and another after that. Federer was human, after all, and the movie shows him coming to grips with that fact as he admits he’ll never be fit enough to play professionally again. On his last day in the gym with his trainer, Federer says of their workouts, “I used to hate it, but now I’ll miss it.” He also says that if he’d known the path that the surgeries would take him on, he never would have had them in the first place.

Later, Federer says of his main rival, Rafael Nadal, that he didn’t like when he came along to challenge him. He liked being up at the top by himself, and he may have even believed that he would be alone on the mountaintop for as long as he pleased. But after some early denial, Federer was forced to accept—first by Nadal and then by Novak Djokovic—that he had legitimate rivals, that he couldn’t rule alone, that he wasn’t a one of a kind phenomenon. All of which makes Federer’s retirement night, and the tears shared with Nadal and Djokovic, a fitting end to the story of a champion who started out standing alone, but in the end found satisfaction and enjoyment in the camaraderie with the rivals he had once fought tooth and nail against.

Federer the Man for All Seasons

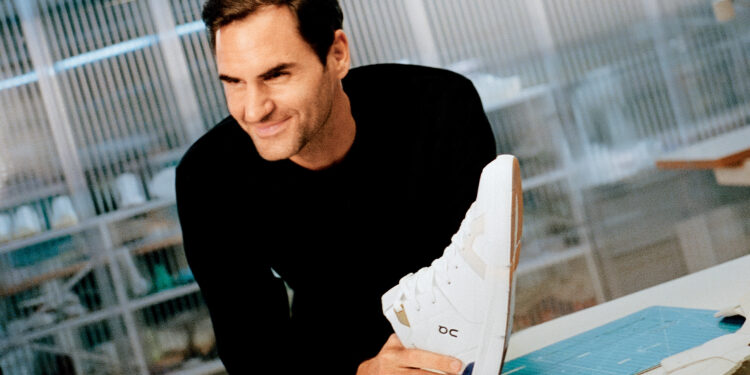

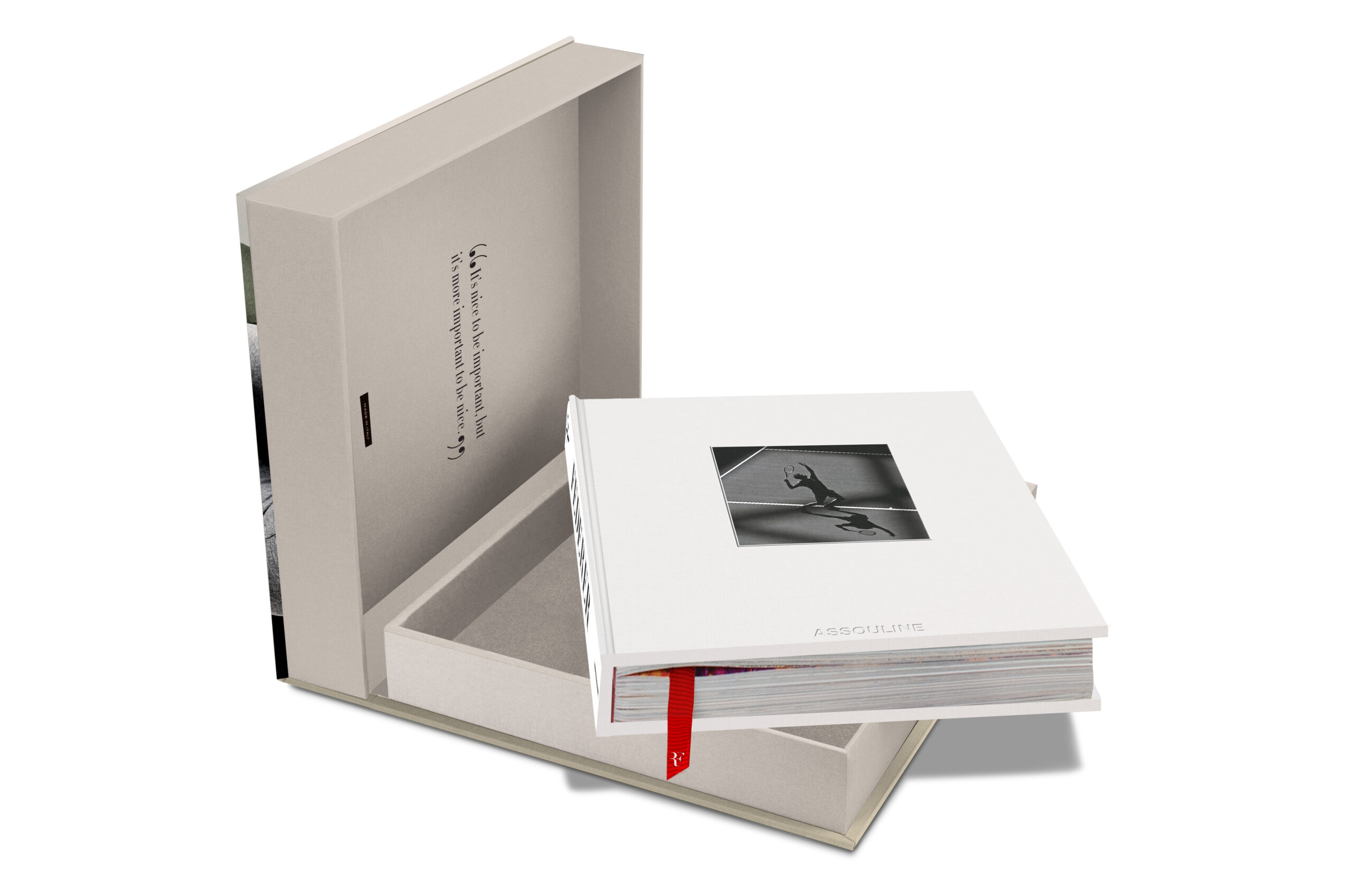

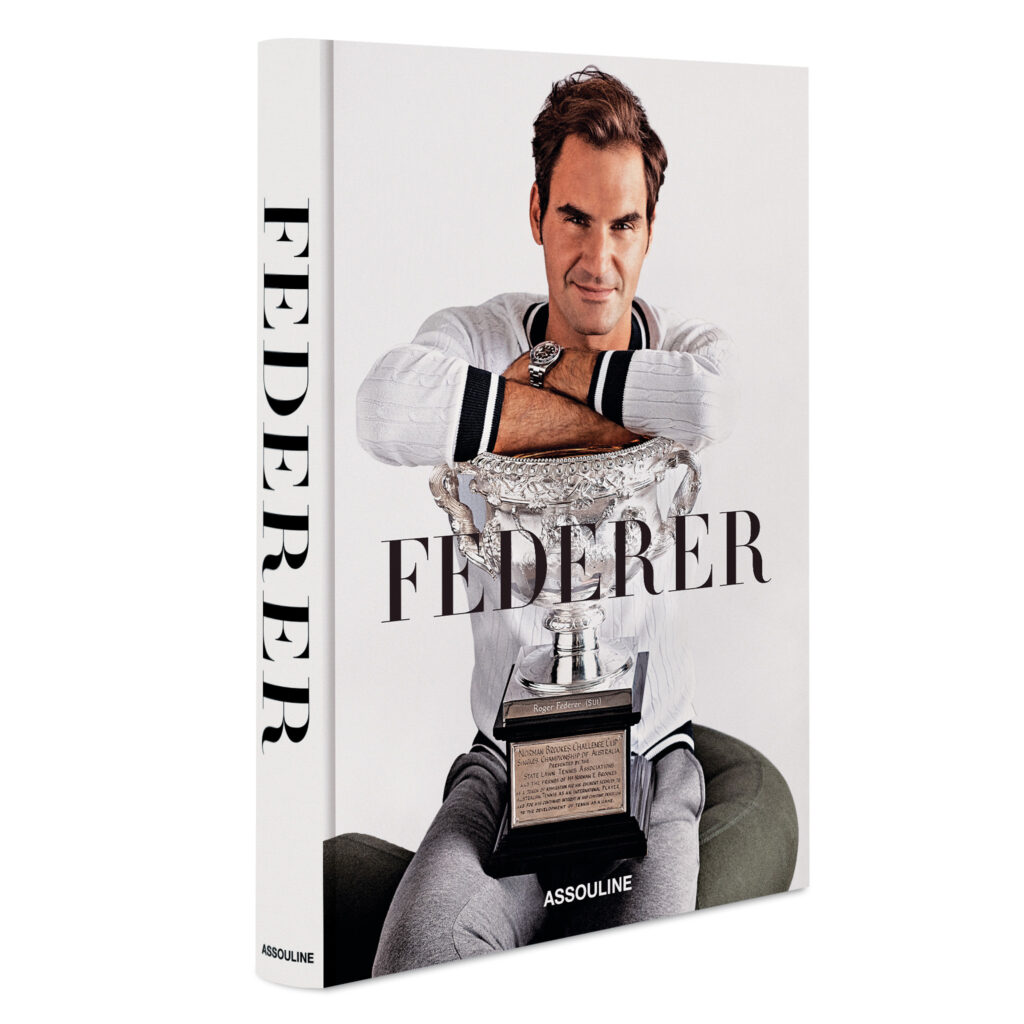

The Swiss great’s summer ended with another documentary-style release: Federer, a coffee-table book from Assouline done in the traditional Assouline style—as big and deluxe as possible. The book may need a table of its own to be properly gazed upon. The man himself appears on the cover looking the way he may want to be remembered: Wearing a Rolex and a classic tennis cardigan, holding the Australian Open men’s trophy, with his full head of hair coolly tousled.

As that cover might indicate, Assouline’s book focuses on his successes. With text by retired German sportswriter Doris Henkel, we get the full Federer story, from his first tennis lessons, to his Grand Slam titles, to his family life, to his work with his foundation. Rather than belabor his legendary loss to Nadal at Wimbledon in 2008, we see celebratory photos from his win over Rafa on the same court the year before.

And why not? His win in 2007 has been unfortunately overshadowed by his defeat the following year. More important, this is a book for Federer’s fans, for anyone who may have just started to forget what it was like to watch him play.

The action shots, naturally, are eye-popping. What I like most, though, are the photos of Federer grinning in all kinds of different settings. With family, with other players, with starstruck fans, in front of posters and billboards of his likeness, and finally, on the last page, of him walking off court and waving, the job over, seemingly with no regrets. In these shots, he looks normal, friendly, happy to be there, never bored or annoyed or affected. If you’ve ever been around Federer for more than a few minutes, you know his laughter and goofy excitement is infectious.

Growing up, and expanding your horizons, is a sub-theme of the book. Federer talks about how far tennis has led him, how many people it allowed him to meet, how many lives he feels like he’s touched, and how much those lives have touched him. Unlike a lot of people who play an individual sport, Federer has always been observant and aware of his surroundings, and that comes across here.

“It’s nice to be important, but it’s more important to be nice.” He didn’t coin the phrase, but he liked it and repeated it and tried to live by it. Seeing it inscribed in Federer took me back to his early, innocent days on tour. But it also made me realize that he never lost that innocence, even as he grew into the icon who is commemorated here.

A wise commencement speaker. An honest athlete accepting his humanity. A paragon of sports and style. The summer of Federer emeritus has been a gratifying one for the fans who may still be mourning his absence from the courts. We know there’ll be more of him to come.