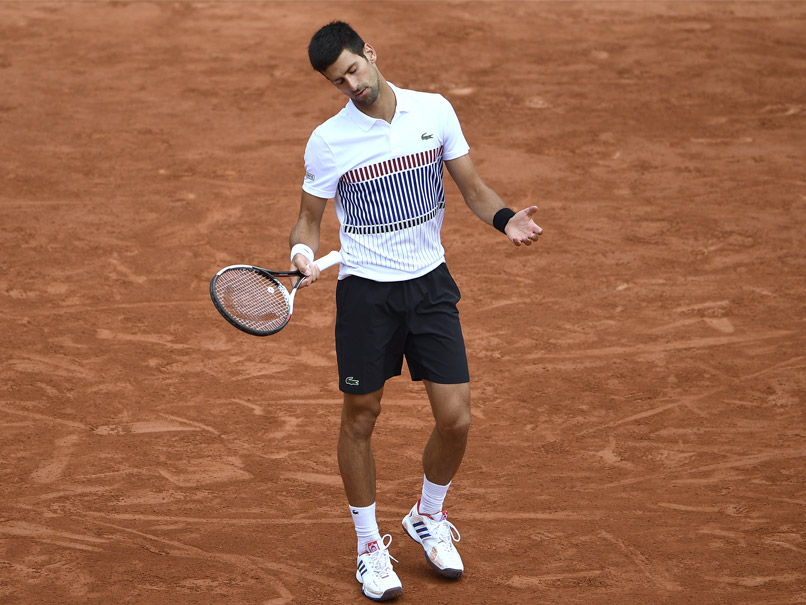

It was the most highly anticipated quarterfinal of the French Open. During the first set, the match lived up to expectations, as the two players traded momentum, and a service break or two, back and forth. But when that set was over, the player who lost it was visibly deflated in the second. By the third, the bottom had fallen out of the match, as the loser waved the white flag of surrender.

That’s a pretty fair description of Dominic Thiem’s one-sided win over Novak Djokovic win in Paris last week. But it’s not the first time we’ve seen this scenario play out in Paris. The paragraph above could also be a recap of Djokovic’s quarterfinal win over Rafael Nadal in 2015.

In both cases, the match marked a low point for the defeated player. Nadal was the five-time defending champion in 2015, and he had beaten Djokovic in each of the three previous French Opens. But over the 12 months since his last victory in Paris, the Spaniard had faltered, even on his beloved clay. That spring, for the first time, he had gone winless through the four French warm-up events in Monte Carlo, Barcelona, Madrid, and Rome. His loss to Djokovic in Paris was the capper, the final proof that the 29-year-old king of clay had been dethroned.

Sound familiar? Djokovic, like Rafa in 2015, was the defending champion at Roland Garros this year, and his run to that title in 2016 had included an easy win over Thiem. But, also like Rafa, Djokovic had faltered over the previous 12 months. During that time he had turned 30, lost his No. 1 ranking, and seemingly lost his motivation. He went winless through the French Open tune-ups events, and his loss to Thiem in Paris, which dropped him out of the Top 3 for the first time since 2009, felt like the capstone to his surprising year-long slump. When it was over, Djokovic hinted that he may need to take time off. Four days later, a rejuvenated Rafa won his 10th Roland Garros title and moved up to No. 2 in the rankings for the first time since 2014.

Nadal and Djokovic have done a role reversal that would have been virtually impossible to foresee in 2015. That’s obviously bad news for Nole as far as his current status goes, but it also points to a question: Can he learn, and take heart, from Nadal’s comeback? If anything, Rafa’s situation looked more dire, and his decline more permanent, in 2015 than Djokovic’s does today.

The first thing that stands out about Nadal’s resurgence is that it took a long time. Even for a Hall-of-Fame player, it isn’t an easy or simple task to rediscover the form of your early 20s as you enter your early 30s. After the 2015 French Open, Nadal continued to struggle: He lost in the second round, to Dustin Brown, at Wimbledon; in the third round, to Fabio Fognini, at the U.S. Open; and in the first round, to Fernando Verdasco, at the 2016 Australian Open. And when Rafa did begin to play well, last spring on clay, he injured his wrist. Nadal seemed to be one more of Father Time’s countless victims.

But Rafa never admitted that defeat. His answer was simple: Keep playing. After each defeat, after each stumble at the end of a match that he seemed to have won, Rafa came into the interview room and said he would keep trying until he got it right. He even added to his schedule, entering tournaments in Hamburg, Beijing, Acapulco, Basel, Buenos Aires, Rio, and Brisbane that he had rarely played before. Rather than curtail his play at the end of the year, as he had in his prime, Nadal plowed ahead through the indoor fall season, a stretch where he has never enjoyed much success.

The result of that effort wasn’t an immediate confidence boost; most weeks ended in defeat for Nadal. But his workload did have one crucial effect: He improved his backhand. Even as he stumbled at the majors in 2016, and even as his forehand continued to be a problem, his backhand became more solid. By 2017, Nadal had begun to use it as a weapon in a way that he hadn’t in the past. That shot turned out to be one of the keys to his wins over Thiem and Wawrinka at Roland Garros this year.

The second change that Nadal made was to hire Carlos Moya to work alongside his uncle Toni. After treading water in 2015 and 2016, Rafa and Toni finally admitted that a new voice and fresh ideas would help, and they were right. Moya, an old friend of Rafa’s, was a good choice, because he was both a fresh voice and a familiar one. He knew what he could change in his game, and what he couldn’t. Seeing that Nadal wasn’t getting much value from his serve, Moya advised him to mix up his speeds and locations. By this spring, those changes had paid off; Nadal’s serve was a major factor in his run through the clay season.

Is Nadal’s success story applicable to Djokovic right now? Grinding it out week after week may not be what the Serb needs or wants to do at this moment; a break from the game actually might help him more. But there’s still a lesson to be learned from Nadal on that front: Once Rafa had slid in the rankings, he stopped worrying about every defeat and made a long-term commitment to getting better. He knew that at 30 he wasn’t going to dominate the way he once had, and he came to accept that even the most painful losses needed to be chalked up as part of the improvement process. Nadal essentially turned himself into a striving young player again, determined to work his way back up the rankings and not worry about his age or his former status. That lunch-bucket mentality may eventually be what Djokovic has to adopt, too. Over the last year, Novak has played his best when he has recaptured the brashness and aggression that propelled him so rapidly up the rankings a decade ago.

As for a new coach, Djokovic has already tried that with Andre Agassi in Paris. Whether that pairing works, or he hires someone else, he can obviously use a fresh pair of eyes on his game. More important, he can use a fresh jolt of enthusiasm and honest analysis in his camp. Even in the matches that Djokovic won in Paris, he played passively; he seemed content to mirror his opponents’ baseline games and outlast them. Djokovic seemed ripe, in other words, for new ideas about how to use his skills and strengths, the same way that Nadal did last year.

The first lesson of Rafa’s resurgence is the same as Federer’s: A great player, even at 30, is never finished improving; with that kind of talent, old weaknesses—Federer’s backhand, Nadal’s serve—can suddenly be turned into strengths. Djokovic has that kind of talent, too.

The second lesson is that to go forward, you may need to go backward. You may need to be willing to do all of the often-frustrating work that got you to the top all over again. And it may not happen overnight, or even over the course of a season.

The third lesson is the easiest to see for Djokovic: In 2015, he broke Nadal down at Roland Garros and knocked him off his clay-court throne. Two years later, the Spaniard is sitting on it again, and may be playing the best tennis of his career. If Roger and Rafa can get back off the mat in their 30s, why can’t Novak?